Abstract: The proper method of wiring an RS-485 network is described, with recommendations for twisted-pair cabling and correctly locating termination resistors. Received waveforms are shown for examples of proper and improper cable termination. Configurations are shown for a simple, single-transmitter/multiple receiver network through multiple transceiver to multibranched circuits.

This application note provides basic guidelines for wiring an RS-485 network. The RS-485 specification (officially called TIA/EIA-485-A) does not specifically explain out how an RS-485 network should be wired. The specification does, nonetheless, give some guidelines. These guidelines and sound engineering practices are the basis of this note. The suggestions here, however, are by no means inclusive of all the different ways that a network can be designed.

RS-485 transmits digital information between multiple locations. Data rates can be up to, and sometimes greater than, 10Mbps. RS-485 is designed to transmit this information over significant lengths, and 1000 meters are well within its capability. The distance and the data rate with which RS-485 can be successfully used depend a great deal on the wiring of the system.

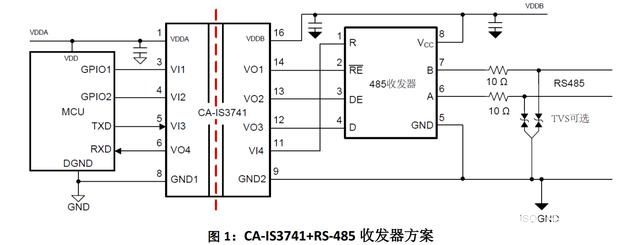

Figure 1. A balanced system uses two wires, other than ground, to transmit data.

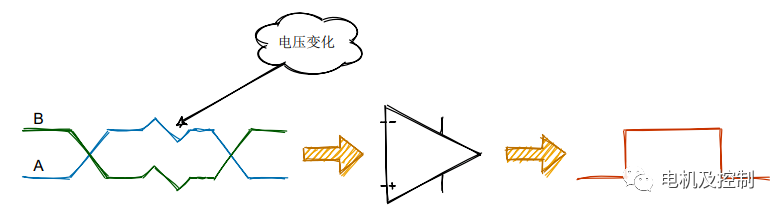

The system is called balanced, because the signal on one wire is ideally the exact opposite of the signal on the second wire. In other words, if one wire is transmitting a high, the other wire will be transmitting a low, and vice versa. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. The signals on the two wires of a balanced system are ideally opposite.

Although RS-485 can be successfully transmitted using multiple types of media, it should be used with wiring commonly called "twisted pair."

Figure 3. Waveform of a 125kHz square wave and its FFT plot.

The resultant high-frequency components of these fast edges coupled with long wires can radiate EMI. A balanced system used with twisted-pair wire reduces this effect by making the system an inefficient radiator. It works on a very simple principle: as the signals on the wires are equal but opposite, the radiated signals from each wire will also tend to be equal but opposite. This has the effect of canceling each other, meaning that there is no net radiated EMI. However, this result is based on the assumption that the wires are exactly the same length and in exactly the same location. Because it is impossible to have two wires in the same location at the same time, the wires should be positioned as close to each other as possible. Twisting the wires so there is a finite distance between the two wires helps counteract any remaining EMI.

A terminating resistor is simply a resistor placed at the extreme end or ends of a cable (Figure 4). The value of the terminating resistor is ideally the same value as the characteristic impedance of the cable.

Figure 4. Termination resistors should be the same value of the characteristic impedance of the twisted pair and should be placed at the far ends of the cable.

When the termination resistance is not the same value as the characteristic impedance of the wiring, reflections will occur as the signal travels down the cable. This process is governed by the equation (Rt-Zo)/(Zo+Rt), where Zo is the impedance of the cable and Rt is the value of the terminating resistor. Although some reflections are inevitable due to cable and resistor tolerances, large enough mismatches can cause reflections big enough to cause errors in the data. See Figure 5.

Figure 5. Using the circuit shown at the top, the waveform on the left was obtained with a MAX3485 driving a 120Ω twisted-pair cable terminated with 54Ω. The waveform on the right was obtained with the cable terminated properly with 120Ω.

Knowing this about reflections, it is important to match the terminating resistance and the characteristic impedance as closely as possible. The position of the terminating resistors is also very important. Termination resistors should always be placed at the far ends of the cable.

As a general rule moreover, termination resistors should be placed at both far ends of the cable. Although properly terminating both ends is absolutely critical for most system designs, it can be argued that in one special case only one termination resistor is needed. This case occurs in a system when there is a single transmitter and that single transmitter is located at the far end of the cable. In this case there is no need to place a termination resistor at the end of the cable with the transmitter, because the signal is intended to always travel away from this end of the cable.

To help the designer of an RS-485 network determine how many devices can be added to a network, a hypothetical unit called a "unit load" was created. All devices connected to an RS-485 network should be characterized in regard to multiples or fractions of unit loads. Two examples are the MAX3485, which is specified at 1 unit load, and the MAX487, which is specified at 1/4 of a unit load. The maximum number of unit loads allowed one twisted pair, assuming a properly terminated cable with a characteristic impedance of 120Ω or more, is 32. Using the examples given above, this means that up to 32 MAX3485s or up to 128 MAX487s can be placed on a single network.

Maxim's MAX13080 and MAX3535 families of transceivers do not require fail-safe bias resistors because a true fail-safe feature is integrated into the devices. In true fail-safe, the receiver-threshold range is from -50mV to -200mV, thereby eliminating the need for fail-safe bias resistors while complying fully with the RS-485 standard. These devices ensure that 0V at the receiver input produces a logic "high" output. Further, this design guarantees a known receiver-output state for the open- and shorted-line conditions.

Figure 6. A one-transmitter, one-receiver RS-485 network.

Figure 7. A one-transmitter, multiple-receivers RS-485 network.

Figure 8. A two-transceivers RS-485 network.

Figure 9. A multiple-transceivers RS-485 network.

Figure 10. An unterminated RS-485 network (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared with a waveform obtained from a correctly terminated network (right).

Figure 11. An RS-485 network with the termination resistor placed at the wrong location (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared to a properly terminated network (right).

Figure 12. An RS-485 network that uses multiple twisted pairs incorrectly.

Figure 13. An RS-485 network that has a 10-foot stub (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared to a waveform obtained with a short stub (right).

References

For technical questions and support: www.maxim-ic.com/support

For samples: www.maxim-ic.com/samples

This application note provides basic guidelines for wiring an RS-485 network. The RS-485 specification (officially called TIA/EIA-485-A) does not specifically explain out how an RS-485 network should be wired. The specification does, nonetheless, give some guidelines. These guidelines and sound engineering practices are the basis of this note. The suggestions here, however, are by no means inclusive of all the different ways that a network can be designed.

RS-485 transmits digital information between multiple locations. Data rates can be up to, and sometimes greater than, 10Mbps. RS-485 is designed to transmit this information over significant lengths, and 1000 meters are well within its capability. The distance and the data rate with which RS-485 can be successfully used depend a great deal on the wiring of the system.

Wire

RS-485 is designed to be a balanced system. Simply put, this means there are two wires, other than ground, that are used to transmit the signal.

Figure 1. A balanced system uses two wires, other than ground, to transmit data.

The system is called balanced, because the signal on one wire is ideally the exact opposite of the signal on the second wire. In other words, if one wire is transmitting a high, the other wire will be transmitting a low, and vice versa. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. The signals on the two wires of a balanced system are ideally opposite.

Although RS-485 can be successfully transmitted using multiple types of media, it should be used with wiring commonly called "twisted pair."

What Is Twisted Pair, and Why Is It Used?

As its name implies, a twisted pair is simply a pair of wires of equal length and twisted together. Using an RS-485-compliant transmitter with twisted-pair wire reduces two major sources of problems for designers of high-speed long-distance networks: radiated EMI and received EMI.Radiated EMI

As shown in Figure 3, high-frequency components are present whenever fast edges are used in transmitting information. These fast edges are necessary at the higher data rates at which RS-485 is capable of transmitting.

Figure 3. Waveform of a 125kHz square wave and its FFT plot.

The resultant high-frequency components of these fast edges coupled with long wires can radiate EMI. A balanced system used with twisted-pair wire reduces this effect by making the system an inefficient radiator. It works on a very simple principle: as the signals on the wires are equal but opposite, the radiated signals from each wire will also tend to be equal but opposite. This has the effect of canceling each other, meaning that there is no net radiated EMI. However, this result is based on the assumption that the wires are exactly the same length and in exactly the same location. Because it is impossible to have two wires in the same location at the same time, the wires should be positioned as close to each other as possible. Twisting the wires so there is a finite distance between the two wires helps counteract any remaining EMI.

Received EMI

Received EMI is basically the same problem as radiated EMI but in reverse. The wiring used in an RS-485 system will also act as an antenna that receives unwanted signals. These unwanted signals could distort the desired signals, which, if bad enough, can cause data errors. For the same reason that twisted-pair wire helps prevent radiated EMI, it also helps reduce the effects of received EMI. Because the two wires are close together and twisted, the noise received on one wire will tend to be the same as that received on the second wire. This type of noise is referred to as "common-mode noise." As RS-485 receivers are designed to look for signals that are the opposite of each other, they can easily reject noise that is common to both.Characteristic Impedance of Twisted-Pair Wire

Depending on the geometry of the cable and the materials used in the insulation, twisted-pair wire will have a "characteristic impedance" associated with it that is usually specified by its manufacturer. The RS-485 specification recommends, but does not specifically dictate, that this characteristic impedance be 120Ω. Recommending this impedance is necessary to calculate worst-case loading and common-mode voltage ranges given in the RS-485 specification. The specification probably does not dictate this impedance in the interest of flexibility. If for some reason 120Ω cable cannot be used, it is recommended that the worst-case loading (the number of transmitters and receivers that can be used) and worst-case common-mode voltage ranges be recalculated to make sure that the system under design will work. The industry-standard publication TSB89, Application Guidelines for TIA-EIA-485-A,1 has a section specifically devoted to those calculations.Number of Twisted Pairs per Transmitter

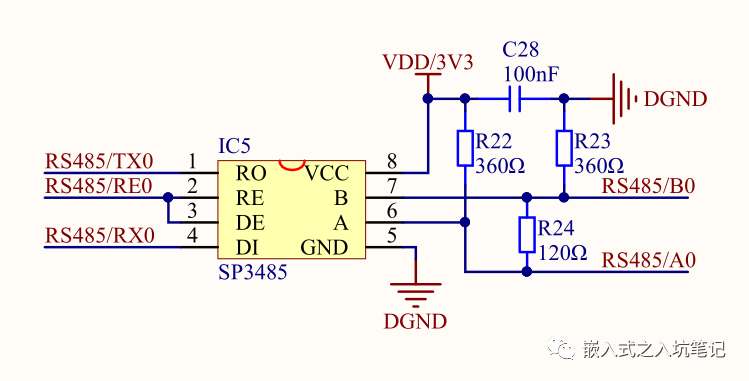

Now that the required type of wire is understood, one can ask, how many twisted pairs can a transmitter drive? The short answer is: exactly one. Although it is possible for a transmitter to drive more than one twisted pair under certain circumstances, this is not the intent of the specification.Termination Resistors

Because of the high frequencies and the distances involved, proper attention must be paid to transmission-line effects. A thorough discussion of transmission-line effects and proper termination techniques is, however, are well beyond the scope of this application note. With this in mind, terminations will be briefly discussed in their simplest form as they relate to RS-485.A terminating resistor is simply a resistor placed at the extreme end or ends of a cable (Figure 4). The value of the terminating resistor is ideally the same value as the characteristic impedance of the cable.

Figure 4. Termination resistors should be the same value of the characteristic impedance of the twisted pair and should be placed at the far ends of the cable.

When the termination resistance is not the same value as the characteristic impedance of the wiring, reflections will occur as the signal travels down the cable. This process is governed by the equation (Rt-Zo)/(Zo+Rt), where Zo is the impedance of the cable and Rt is the value of the terminating resistor. Although some reflections are inevitable due to cable and resistor tolerances, large enough mismatches can cause reflections big enough to cause errors in the data. See Figure 5.

Figure 5. Using the circuit shown at the top, the waveform on the left was obtained with a MAX3485 driving a 120Ω twisted-pair cable terminated with 54Ω. The waveform on the right was obtained with the cable terminated properly with 120Ω.

Knowing this about reflections, it is important to match the terminating resistance and the characteristic impedance as closely as possible. The position of the terminating resistors is also very important. Termination resistors should always be placed at the far ends of the cable.

As a general rule moreover, termination resistors should be placed at both far ends of the cable. Although properly terminating both ends is absolutely critical for most system designs, it can be argued that in one special case only one termination resistor is needed. This case occurs in a system when there is a single transmitter and that single transmitter is located at the far end of the cable. In this case there is no need to place a termination resistor at the end of the cable with the transmitter, because the signal is intended to always travel away from this end of the cable.

Maximum Number of Transmitters and Receivers on a Network

The simplest RS-485 network is comprised of a single transmitter and a single receiver. Although useful in a number of applications, RS-485 allows for greater flexibility by permitting multiple receivers and transmitters on a single twisted pair.2 The maximum number of transceivers and receivers allowed depends on how much each device loads down the system. In an ideal world, all receivers and inactive transmitters will have infinite impedance and will not overload the system in any way. In the real world, however, this is not the case. Every receiver attached to the network and all inactive transmitters will add an incremental load.To help the designer of an RS-485 network determine how many devices can be added to a network, a hypothetical unit called a "unit load" was created. All devices connected to an RS-485 network should be characterized in regard to multiples or fractions of unit loads. Two examples are the MAX3485, which is specified at 1 unit load, and the MAX487, which is specified at 1/4 of a unit load. The maximum number of unit loads allowed one twisted pair, assuming a properly terminated cable with a characteristic impedance of 120Ω or more, is 32. Using the examples given above, this means that up to 32 MAX3485s or up to 128 MAX487s can be placed on a single network.

Failsafe Bias Resistors

When inputs are between -200mV and +200mV, receiver output is "undefined". There are four common fault conditions that result in the undefined receiver output that can cause erroneous data:- All transmitters in a system are in shutdown.

- The receiver is not connected to the cable.

- The cable has an open.

- The cable has a short.

Maxim's MAX13080 and MAX3535 families of transceivers do not require fail-safe bias resistors because a true fail-safe feature is integrated into the devices. In true fail-safe, the receiver-threshold range is from -50mV to -200mV, thereby eliminating the need for fail-safe bias resistors while complying fully with the RS-485 standard. These devices ensure that 0V at the receiver input produces a logic "high" output. Further, this design guarantees a known receiver-output state for the open- and shorted-line conditions.

Examples of Proper Networks

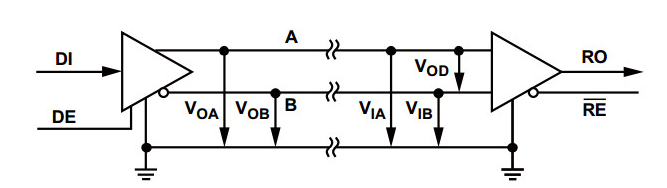

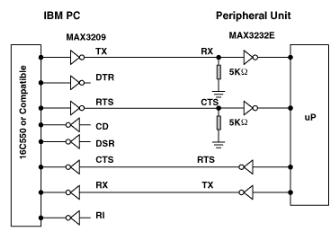

Given the above information, we are ready to design some RS-485 networks. Here are a few examples.One Transmitter, One Receiver

The simplest network is one transmitter and one receiver (Figure 6). In this example, a termination resistor is shown at the transmitter end of the cable. Although unnecessary here, it is probably a good habit to design-in both termination resistors. This allows the transmitter to be moved to locations other than the far end, and permits additional transmitters to be added to the network if that becomes necessary.

Figure 6. A one-transmitter, one-receiver RS-485 network.

One Transmitter, Multiple Receivers

Figure 7 shows a one-transmitter multiple-receivers network. Here, it is important to keep the distances from the twisted pair to the receivers as short as possible.

Figure 7. A one-transmitter, multiple-receivers RS-485 network.

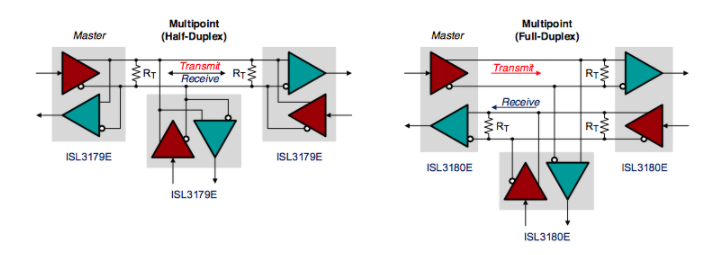

Two Transceivers

Figure 8 shows a two-transceivers network.

Figure 8. A two-transceivers RS-485 network.

Multiple Transceivers

Figure 9 shows a multiple-transceivers network. As with the one-transmitter and multiple-receivers example in Figure 7, it is important to keep the distances from the twisted pair to the receivers as short as possible.

Figure 9. A multiple-transceivers RS-485 network.

Examples of Improper Networks

The diagrams below are examples of improperly configured systems. Each example shows the waveform obtained from the improperly designed network, and compares that waveform from a properly designed system. The waveform is measured differentially at points A and B (A-B).Unterminated Network

In this example, the ends of the twisted pair are unterminated. As the signal propagates down the wire, it encounters the open circuit at the end of the cable. This constitutes an impedance mismatch, thus producing reflections. In the case of an open circuit (as shown below), all the energy is reflected back to the source, causing the waveform to become very distorted.

Figure 10. An unterminated RS-485 network (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared with a waveform obtained from a correctly terminated network (right).

Wrong Termination Location

Figure 11 shows a termination resistor, but it is located in a position other than the far end of the cable. As the signal propagates down the cable, it encounters two impedance mismatches. The first occurs at the termination resistor. Even though the resistor is matched to the characteristic impedance of the cable, there is still cable after the resistor. This extra cable causes a mismatch and, therefore, reflections. The second mismatch is at the end of the unterminated cable, leading to further reflections.

Figure 11. An RS-485 network with the termination resistor placed at the wrong location (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared to a properly terminated network (right).

Multiple Cables

There are multiple problems with the layout in Figure 12. The RS-485 drivers are designed to drive only a single, properly terminated twisted pair. Here, the transmitters are each driving four twisted pairs in parallel. This means that the required minimum logic levels cannot be guaranteed. In addition to the heavy loading, there is an impedance mismatch at the point where multiple cables are connected. Impedance mismatches again mean reflections and, therefore, signal distortions.

Figure 12. An RS-485 network that uses multiple twisted pairs incorrectly.

Long Stubs

In Figure 13, the cable is properly terminated and the transmitter is driving only a single twisted pair. However, the connection point (stub) for the receiver is excessively long. A long stub causes a significant impedance mismatch and thus reflections. All stubs should be kept as short as possible.

Figure 13. An RS-485 network that has a 10-foot stub (top) and its resultant waveform (left), compared to a waveform obtained with a short stub (right).

References

- TSB89, Application Guidelines for TIA/EIA-485-A, can be found by searching for the standard at www.global.his.com.

- For more information, see TIA/EIA-485-A Electrical Characteristics of Generators and Receivers for Use in Balanced Digital Multipoint Systems, which can be found by searching for the standard at www.global.his.com.

For technical questions and support: www.maxim-ic.com/support

For samples: www.maxim-ic.com/samples

電子發燒友App

電子發燒友App

評論